One of the critical yardsticks in measuring the developmental progress of a nation is its level of infrastructure painstakingly built to propel economic growth and mass prosperity. Since time immemorial, both developing and developed nations have always considered strategies to push their infrastructural dreams, optimising varying chains of finance that will, in turn, maintain development and boost such nations’ progress.

As countries look for ways to address the seemingly unending infrastructural gaps even in developed nations, the Sukuk funding option comes as a way of also looking beyond the conventional finance models. Simply put, Sukuk is an offshoot of the Islamic model of finance. It is that which seeks to provide interest-free credit opportunities for multi-faceted development purposes. Since Islam forbids Riba known as Interest, Sukuk presents a clear avenue to borrow without thinking of paying a kobo extra from what is lent.

Sukuk Explained

Also known as the Islamic Financing Model, a Sukuk is an Islamic debt instrument wherein the finance provider has ownership of real assets and earns a return sourced from those assets. This contrasts with conventional bonds where the investor has a debt instrument earning the return predominately via the payment of interest (riba).

The novel idea presents a clear avenue to borrow without thinking of paying a kobo extra from what is lent. To a layman, Sukuk may be legally characterised as investment certificates and the owners of such certificates – sukuk holders – are entitled to earn revenue based on the performance of the investment that the certificates are attached.

To ensure compliance with Islamic law, the underlying legal relationship of sukuk cannot be a loan because of the riba prohibition concerning the interest accrual of a loan. Therefore, the underlying legal relationship must be based on an Islamic law-compliant transaction, such as murabaha (sale and buy back), ijara (sale and lease-back, lease and lease-back, forward lease, etc.), salam (advanced payment), istisna (sale of specified manufactured goods for delivery upon completion), musharaka (partnerships where profits are shared in line with agreed upon ratios whilst losses are shared according to contributed capital), mudharaba (profit sharing where a rab al-mal or investor contributes capital and a mudharib or manager contributes his time and efforts), and wakalah (agency).

Why is Islamic finance on infrastructure relevant?

The sukuk model resonates well with simple finance methods that individuals, organisations and governments across the world adopt in resource management, allocation and control. For instance, a state government in Nigeria with a monthly revenue of N10 billion from both FAAC Allocation and IGR cannot attend to the needs of providing potable water for an average population of 2 million people. If the government cannot provide water with N10bn, how would it now attend to other important sectors like Security, Health, Agriculture, Public Transportation and the big one – Infrastructure, without looking in the way of credit facilities?

Citizens want good schools, roads, water, electricity and every basic amenity that will make their lives better from their government. With varied legislation of many societies not opposed to government taking virement to fund its projects and activities, conditions of repayment have always pitched the leadership against the people, especially in this age where debates about backdoor neocolonialism and slave trade with international money lenders such as the Bretton woods institutions continue to dominate credit finance forums the world over.

This is where the funding option of Sukuk comes in, especially in providing the basic infrastructure that will make life better for the people. With its structured repayment plan, Sukuk has proven to be effective, drawing inferences from a template of due diligence and transparency that makes its bond issuance seamless devoid of the guidelines applicable to conventional bonds.

From available information, countries like Malaysia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia to mention but a few have used the Sukuk gateway to fund large-scale infrastructure projects, developing strong regulatory frameworks, innovative sukuk structures, and broad investor participation. This implies that Sukuk does not just help to build infrastructure, but attract large investment from investors, who are simply looking for a solid and corruption-free environment that will make such investments thrive.

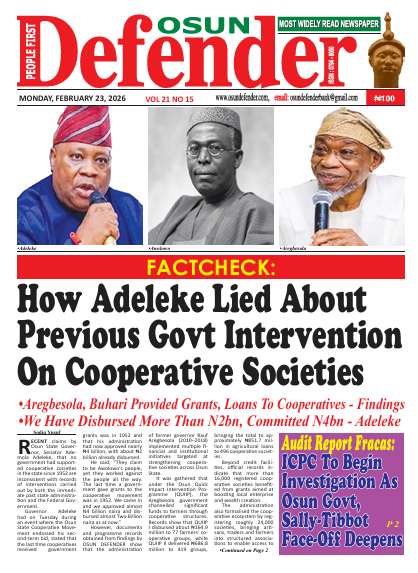

The Osun Sukuk Model and its Transparency

The administration of Governor Rauf Adesoji Aregbesola (2010 – 2018) made the audacious yet bold move to tap into optimising the benefits of Islamic financing. When Osun issued its Sukuk in 2013, only a few African countries had Sukuk and many did not even have a regulatory framework for Sukuk issuances. In addition, it was only in the wake of the imminent Osun State issue that Nigeria’s Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) introduced rules that created a framework for selling and investing in Sukuk. (Read more). While the 2013 approval came shortly months after it approved new guidelines for the operation of takaful (Islamic insurance/banking) for Nigeria, it was only in 2016 that the commission and the Debt Management Office (DMO) came together to officially collaborate on the issuance of Nigeria’s first foreign Sukuk on behalf of the Federal Government.

During the years that the bond lasted, Osun raised a sukuk bond worth N10 billion (some $62 million) from the capital market to fund educational development – the first of such in Africa after Gambia and Sudan. The schools’ infrastructure built with Sukuk are Wole Soyinka High School, Ejigbo, Ataoja High School, Osogbo, Fakunle Unity High School, Osogbo, Oduduwa High School, Ile Ife, Ila High School, Ila-Orangun, Adventist High School, Ede, Iwo High School, Iwo, Akinorun High School, Ikirun and Ayedaade High School, Ikire.

On the transparency of its utilisation in Osun’s case, its structure in making the underlying income-generating assets were the schools. The SPV then turned around and leased the schools to the state government, and earned rent from this agreement, which was then used to pay the Sukuk holders. When the lease expired, the state government bought the schools outright and the funds were returned to the Sukuk holders as principal. The same model was adopted when the Federal Government rolled out its own bond. (See more) (2)

The compelling fact about Sukuk is that its projects are well-implemented and completed, unlike the conventional funding system where projects face greater pressure to deliver on time, potentially increasing the risk of delays or underperformance, especially when unforeseen issues such as the fluctuation of the exchange rate arise. Factors like Shariah compliance and ethical constraints, risk sharing in sukuk, availability of funding legal and regulatory framework make its adoption further credible.

Islamisation and the Sukuk Opportunity For Nigerian States

For all the potential sukuk holds for Nigeria, the biggest obstacle has been ignorance. When Osun rolled out its Sukuk, it received significant backlash from Christian organisations who expressed displeasure with the introduction of a Sharia-compliant financial instrument accusing those who adopted it of trying to Islamise Nigeria.

The challenge is that many of the people who criticise it do not know that Sukuk is more like any of the financial instruments used to access either credit, interest, or any form of finance. The major distinguishing criteria between Sukuk and others is its root in Sharia principles. Interestingly, the Sukuk market is open to all Nigerians without any religious restrictions.

While Religion will continue to remain a sensitive issue in Nigeria, continuous education is required to sit Nigerians down on the basic principles of Sukuk using varied examples of nations like the United Kingdom, Singapore, and Germany who have all issued Sukuk in the last decade. It must also be noted that states in Nigeria’s South East region, predominantly dominated by Christians, are looking for funding options for infrastructure projects, especially through the Islamic Development Bank (IfDb) which is another form of Sukuk because of its potential in accurate verification, transparency and accountability.

Conclusion

Nigeria has a long way to go in closing its infrastructure gap. However, the continuous success of Islamic finance in other countries and the tiers of government where it has been successful so far, makes it more plausible for more states in the country to learn about and accept it as a financial tool for development, more importantly with the startling reality of continuous low oil revenue. With the undeniable fact that government as an entity is not a religious propagating institution, all sources of virement for development are welcome. Whether from Sango or Ifa, Bible or the Quran, as long as it can build schools and bridges in a transparent and accountable model, the most important detail is progress and growth.

Sodiq Yusuf is a trained media practitioner and journalist with considerable years of experience in print, broadcast, and digital journalism. His interests cover a wide range of causes in politics, governance, sports, community development, and good governance.