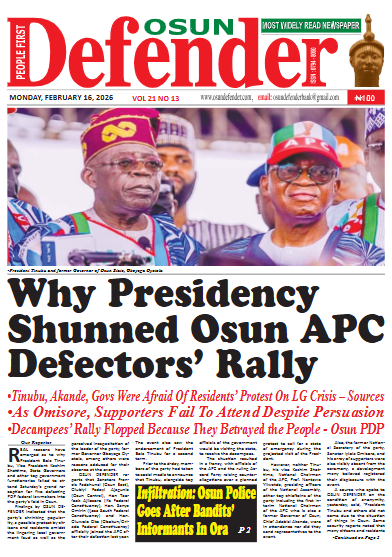

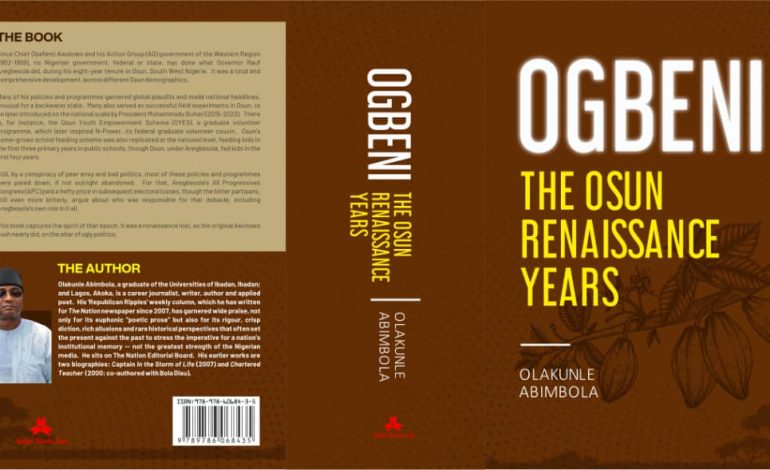

A REVIEW: O’ School And Opon Imo

“Ogbeni: The Osun Renaissance Years is a book written by a prominent Nigerian columnist, Olakunle Abimbola. The book details the administration of former Governor of Osun State, Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola, and the ideological leanings that shaped his approach to governance. Here is an excerpt from Chapter 10 of the book”

The brief that Governor Aregbesola gave Gboyega Adeeyo, chartered engineer and consultant-in-chief for the Osun schools intervention project, was a furious race against time. Adeeyo was the overall consultant under whose guidance all the new schools were designed, constructed, and delivered.

When I started the job, the Governor told me he had 356, 000 students he had to put in classrooms – and that was 12 years ago. When I came, there were really no schools. I went around, took pictures and I showed him. Every school that I went to was dilapidated. Some didn’t even have roofs. Some had collapsed roofs, but students were studying with them. So, he said he wanted as many classrooms as possible. But we only built 11 mega-schools that could house 3, 000 each. Three thousand multiplied by 11 only gives you 33, 000. What’s 33, 000 out of 350, 000? You have not even scratched the surface! So, when people say the schools are too big – too big for what?”

That was how stark and near-hopeless the Osun public education horizon looked. But despite the constraint of time and funding, something else was sacred and must not be breached: every material must be sourced from Osun. Not only that: everyone that worked on the project, from the consultant-in-chief himself, must either be an Osun indigene or must work in the state. The idea, the Governor told Adeeyo, was for the massive school projects to give the local economy a massive kiss of life. For too long, that economy had been in a limbo.

Adeeyo himself, though now a global citizen based in the United States, as cosmopolitan as they come, was a native from Ede. But all the other professionals and resource persons he would hire – architects, quantity surveyors, engineers, masons, carpenters and allied building technicians, from the highest expert to the lowest artisan – must be Osun-based. The Governor wanted the locals to benefit from the crucial hands-on training that such a massive intervention work could offer, to better drive whatever they did in the future. By that, he reckoned, their capacity would be greatly enhanced; and the Osun economy greatly deepened.

“Can I, at least,” Adeeyo wanted to know, “bring in my immediate deputy?”

“No” was the flat response from the Governor.

Then, the Governor made an otherwise casual remark which nevertheless struck a chord with Adeeyo; and switched his sympathy towards the Governor’s vision.

“Look at you” he told him. “Everyone here likes you. They love the way you speak. Even if that is the only trait you can pass to those to work under you, you would have made my day”!

As it turned out, many of Adeeyo’s recruits, later turned professional wards, took away much more than the Governor’s cherished Adeeyo elocution. There was a particular one, a female professional, then married with a child who had, all her life, never even stepped out to Lagos.

“She had never seen the lagoon, or such a large body of water. But in the course of our work, we had to come to Lagos for a meeting, and that was when she first saw the lagoon. On the Third Mainland Bridge,” Adeeyo recalled her goose pimples, “she was so anxious and fidgety!”

READ: Government Unusual

Ruth Opatola was another charge that used O’School as a stepping stone to self-improvement. Adeeyo dubbed her an “Osogbo babe”. Ruth, who had earned a first degree in Architecture, from the Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife, was hired as one of the project architects. She was the quintessential native: born and bred in Osogbo, schooled in Osun and climaxed her education at the nearby OAU. Again, to Osogbo she returned, for her career and professional nourishment. But while working on the project, she applied for post-graduate studies at a university in the United States and she got admitted. Adeeyo served as her guardian and guarantor, paving her travel path and guiding her professional dreams. Eventually, Ruth got to travel — for the very first time, outside Nigeria.

“She graduated with a higher degree and she now lives in Silicon Valley,” Adeeyo gushed, 12 years after the project that linked the guardian with his protégé. “Everyone knew her back then as Osogbo babe. But if you see Ruth today, even from the way she speaks, no one can call her an Osogbo babe again.”

Still, Aregbesola’s strict policy of sourcing project personnel and materials from Osun did not always end well. Take the collapse, for instance, of the ceilings of the school hall, at the newly completed Wole Soyinka Government High School, Ejigbo. It was the very first of the mega model schools, delivered in 2014. Adeeyo blamed the accident on substandard steel. It could not support the dead weight of the ceiling. So, the ceiling came crashing down.

No thanks to that policy, those materials were bought in Osogbo, while better quality ones were readily available in Lagos. That accident provided furious fare for the Osun political opposition supported by their media confederates, eager to bad-mouth the school projects. But the accident led to a re-design: reducing the structures’ dead weight to what locally available steel in Osogbo could carry. Though that accident was unanticipated and unfortunate, Adeeyo said the slew of projects was planned with continuous feedback and design amendment mechanisms. That way, the project team could make corrections as the projects advanced; and more schools were constructed and delivered. For the collapsed hall, however, the consultant-in-chief took full responsibility. He pulled down the structure and rebuilt it from scratch – all from his own pocket, without costing the state government a dime. But he redesigned the schools built afterwards to the strength of the locally available materials. So, there could be no future talk of collapse, or structural failure, of any of the schools.

“Engineering,” he explained, “is the only field that boasts deductive logic. I can say two plus two equals four. I have added two plus two, so it must equal four. With that I can confidently walk away,” he declared, adding that a doctor that performs a surgery was less sure of its success than an engineer that puts up a structure. He, therefore, pooh-poohed any suggestions that the model schools, particularly the high-capacity high schools, could have suffered structural impairments. From the Ejigbo experience, they should have failed much earlier, if they were to fail due to any design error. In any case, it would appear ludicrous to him that the solution to a structural challenge, neither glaring nor fully proven, was a suggestion to demolish the building!

Adeeyo is a 1984 graduate of Civil Engineering from the University of Lagos. As a pupil engineer with Morgan Monitoring, an engineering firm, he was involved in the design and delivery of the university’s high rise Senate Building; among other projects he had been involved in, home and abroad, in his storied professional career. That has taken him all over the world, from his base in the United States of America.

Despite that accident at the Wole Soyinka Government High School, Ejigbo, Adeeyo declared the school intervention projects as hugely consequential: for boosting public education in Osun, developing willing local professionals and giving the once comatose state economy a healthy jab. Still, he decried the general work culture: “People steal too much around here,” he rued. “You literarily had to stay up 24-7 to check such thefts!”

Indeed, Governor Aregbesola was in a hurry to deliver those schools; and get Osun pupils in them. But conventional buildings took time – for the cement to set, the frames to properly fit in, not to talk of the plumbing and internal décor to be carefully put in place. In his hurry, some contractors sold to the Governor a pre-fab concept, which could deliver a mega-school in six months, at most. The eager Governor jumped at that prospect; and that explained the three pre-fab mega-schools: in Osogbo, in Ilesa and in Iwo. The Iwo one ironically was not completed due to hostile local politics. After much earth work had been done at the Baptist High School original site, the Baptist Mission rejected the idea. As a result, the Iwo community suggested that the project be moved to Iwo Grammar School. That was done. But the money sunk into the aborted site left a permanent hole in the school’s funding, since the money available for the project was fixed – a Sukuk bond, with its rigorous terms – with no augmentation from elsewhere. That explains why the Iwo mega-school project remained uncompleted, some four years after Aregbesola’s exit from government.

At Ejigbo, however, the pupils clearly shared the Governor’s impatience to move into the new classrooms. While the politicians were planning a grand ceremony to inaugurate the newly completed Wole Soyinka Government High School, the local pupils simply flocked in to occupy the classrooms! Such was their ramshackle school experience that they couldn’t wait to experience life in the glittering, new school complex.

READ: {MAGAZINE} Aregbesola, The Colossus: March On @ 63

O’School Committee

Otunba Layi Oyeduntan, chair of the O’School Committee, relived the cherished but vanished memories of his own school-going youth, in Osogbo and nearby towns. O’School, a project management committee under the Osun Deputy Governor’s Office, from 2012, worked closely with Adeeyo and his team of consultants and contractors to deliver the schools: brand new, redesigned or refurbished.

“When we were small children, schools were the most beautiful structures in the neighbourhood – the only painted buildings, in fact. They were a model: an attraction for pupils to want to go to school.” Not anymore.

Otunba Oyeduntan recalled a particular troubling instance: “I had pictures of some of the schools built by Oyinlola two years before then. In a particular one, goats had left gaping holes in the walls, after scratching and rubbing their bellies on them, in search warmth! That showed poor and shoddy work, when those schools were built. I went to school here,” he stressed, “and such rickety structures wouldn’t have been fair to either the teachers or the pupils of our day.”

That gloomy survey influenced the new Aregbesola government to take steps to radically “influence the structural environment”; and make schools attractive to Osun children and youths again. That explained the O’School concept of transformative public schools – a sweeping departure from the routine add-up of three-classroom blocks to an already run-down school environment.

But from rural Osun came even a more depressing sight, with rural poverty writ large on scrawny, hungry-looking children and their odd uniforms: “You’ll go into schools and find pupils wearing buba ankara [native fabric tops] tucked into a khaki short; or blue shirts tucked in sooro [Yoruba native pair of trousers]. Forget everything else,” he declared, “it was rural poverty with capital ‘R’!”

Then, the screaming hunger at lunch time, the near-hopelessness of it all in a cramped class and the heavy toll on the poor teachers! “The kids leave home without eating. The female teachers would cry because of the plight of the children. Many of them were forced, despite their own modest means, to buy food for their starving pupils.”

Those depressing sights forced two additional decisions, aside from a radical upgrade of the school buildings and a revamp of the learning environment. One: the government decided to feed as many of the pupils that it could afford. Two: it also decided to provide pupils, in Osun public schools, free school uniforms, particularly those in the rural areas; even if both challenges were not limited to the rural areas alone.

Otunba Oyeduntan flinched at the general misery that assaulted the touring O’School Committee members: “You needed to see the kind of school rooms! There was no way,” he swore, “any decent person could be brought out of those environments. The teachers knew it. The previous government saw it. We all saw it and knew it – and almost gave up. How,” he wondered, “do we raise the billions [of Naira] needed to fix these multiple educational problems?”

Despite that looming funding challenge, there was a near-unanimous policy thinking that Osun public schools needed “wholesale transformation.”

That was the huge challenge that faced the new Aregbesola government on the education front. But the troubleshooting all started with the Education Summit, under the chairmanship of Nobel Laureate, Prof. Wole Soyinka. It held in February 2011 – less than three months after the administration’s 27 November 2010 take-over date.

Osun Education Summit

The Osun Education Summit was held at the University Auditorium, Osun State University main campus in Osogbo, between 7 and 8 February 2011. Its theme was “Resolving the Education Crisis in Osun State: Bridging Analysis and Implementation Gaps”.

From its communiqué, the summit was “attended by over 1, 000 participants from all over Nigeria and from Nigerians in the Diaspora. The Summit received and reviewed 42 memoranda and 11 business proposals from different stakeholders and the general public.” Aside from Summit Chair, Prof. Wole Soyinka, other high-grade attendees were Chief Bisi Akande, former Governor of Osun but then the National Chairman of the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), the state’s new ruling party. Chief Akande was represented by Sooko Adeleke Adewoyin, his Deputy when Akande was Osun Governor, after the impeachment of Otunba Iyiola Omisore. The keynote address came from Prof. Oye Ibidapo-Obe, a former Vice Chancellor of the University of Lagos and then President, Nigeria Academy of Science. Mrs Modupe Ajayi-Gbadebo, a famous journalist and one-time political editor at the iconic but defunct Daily Times, was the chair, Communiqué Drafting Committee; while O. O. Dada was summit secretary.

To resolve Osun’s education challenges, the summit looked into quality assurance and capacity building, the vital role of stakeholders in the education sector, funding approaches, early childhood and basic education, curriculum implementation for functional and entrepreneurial education, special education, the key place of language in education, teachers’ welfare, vastly improved schools environment and general learning readiness by pupils and students.

One of its key recommendations, on primary/secondary education, gave birth to the O’School Committee. The summit communiqué’s exact words: “That Government should set up a task force, with adequate representation of implementing agencies on education, to oversee and monitor the rehabilitation and reconstruction of schools.”

Another crucial recommendation was the call to leverage information and communications technology (ICT) to improve teaching and learning. That must have inspired Opon Imo, the computer “tablet of knowledge” hailed when it was introduced as an innovative teaching and learning tool.

Yet, another recommendation went thus: “that the Labless Science (Skill G) kits of innovative science, mathematics and technology teaching/learning should be reviewed while emphasis should be laid on building proper science laboratories.” This recommendation drove the investment in science laboratories in the newly built Osun public schools during the Aregbesola tenure.

Indeed, this departure from the shot-gun approach to science education, which hitherto was becoming a disturbing norm, delivered a rather inspiring low-hanging fruit. On 16 March 2020, Master Akintade Abdullahi, an Osun public school pupil, won the National Examination of 774 Young Nigerian Scientists Presidential Award, organized by the Federal Ministry of Science and Technology. That win, aside from the commemorative plaque, fetched the winner – best boy (or girl) scientist in all of Nigeria – a presidential scholarship, up to PhD level.

Abdullahi was a pupil of Osogbo Grammar School (formerly Government High School, Oke Fia, Osogbo but since renamed by the Oyetola government); and he represented Osogbo Local Government, one of the 774 local governments of Nigeria, listed in the 1999 Constitution. Osogbo Government High was one of the 11 high-capacity high schools that the Aregbesola administration built. The school itself was inaugurated on 1 September 2016; and Abdullahi’s win came less than four years after it admitted pupils – the earliest signals yet, that the massive investment in glittering, model public schools, with state-of-the-art science laboratories during the Aregbesola years, held the key to the Osun education renaissance, after many years of avoidable slump.

As the other 10 high-capacity high schools, the Osogbo Government High School is a 3,000-capacity school complex: “72 classrooms of 49 square-metre, each capable of sitting 49 pupils; six offices for study groups; six laboratories, 18 toilets each for girls and boys, a science library, an arts library, facility manager’s office, bookshop and sick bay.”

In general practical terms, the O’School educational reforms were carried out in six major areas:

- Revamped school infrastructure.

- Opon Imo.

- School reclassification into Elementary, Middle, High and tertiary institutions.

- Unified school uniforms for Elementary, Middle and High schools.

- O’Meal: the Osun home-grown school feeding programme.

- Enhanced sports and other co-curricular activities, epitomized by a vibrant calisthenics programme in public schools.

As other Aregbesola-era programmes, most of these six new pillars were, on the surface, education policies. But their roots lay deeply buried in challenging social issues and how to surmount them.

O’Meals: was tied to reducing the hunger and slaking the thirst of the children from Osun’s most vulnerable homes, aside from deliberately creating a steady market for the produce of their farmer-parents: Osun crop farmers, poultry owners, fish farmers and animal breeders.

School reclassification: one of its reasons was to remove the meal-time torture of Primary 5 and 6 pupils, not covered by the O’Meals school feeding regime. The other, more fundamentally, was to ensure that pupils, in elementary schools particularly, trekked no more than 50 metres or at most 500 metres, before arriving school. A similar criterion also applied to middle school pupils, though their transiting distance was longer. As for the senior boys and girls of the high schools, they could shuttle over longer distances. Aside from studying to earn their terminal certificates and pass their qualifying examination into universities, polytechnics and colleges of education, the Osun reforms were also designed to condition the high school pupils for tertiary education – near home or far.

Unified school uniform policy: an initial two pairs were given free to each pupil – elementary, middle and high schools. So, the unified uniform policy was designed to prevent poverty from shrinking school enrolment. The mass production of these uniforms was also to provide training, empowerment and job opportunities for Osun tailors and allied guilds. So, abolishing or tweaking any of these pillars could reverberate, with negative consequences, beyond the education sector.

The O’School reforms were put under the direct charge of Deputy Governor Grace Titilayo Laoye-Tomori, who also doubled as Governor Aregbesola’s first-term Commissioner for Education.

“It wasn’t anything political but a genuine desire to make an impact,” Otunba Oyeduntan explained. “That is why,” he added, “the Deputy Governor was put in charge. You don’t go higher than that in the cabinet.”

Model schools

The revamped school infrastructure was the greatest splash of new school buildings, aside from the renovation of old structures, in the history of Osun. It was little wonder then, that those schools (urban, suburban or rural) dominated the Osun landscape; and were more visible than any other – with the possible exception of new roads.

In all, 3, 685 new classrooms were built, under the O’School reforms, which the administration rightly dubbed “radical”, for its sweeping change of the Osun public school horizon. This grand number included 67 brand new model elementary schools, spread all over the state’s 30 Local Governments and one Area Office, 49 new middle schools and 11 high capacity high schools – three in Osogbo, and others, (one each) spread across Ede, Ile-Ife, Ila-Orangun, Ilesa, Ikirun, Gbongan, Iwo and Ejigbo. Indeed, Ejigbo had the distinction of housing the first of such model high schools to be completed and inaugurated: the Wole Soyinka Government High School, Ejigbo, named after the Nobel Laureate, who chaired the Osun Education Summit, which deliberations midwifed the school reforms.

If Ejigbo was the first to breast the tape, Iwo had the misfortune of hosting the only uncompleted one, among the eleven. After the government wasted lead time trying to plant the new school on the grounds of Baptist High School, Iwo – but faced resistance from the Baptist Mission – the Iwo community suggested an alternative site for the new school. The project was then moved to Iwo Grammar School grounds which, had it been completed, would have hosted the brand new Iwo Government High School. Iwo Grammar School (founded 2 March 1964) was famous for its boys’ footballing prowess, as exhibited during the Western Region/Western State Principals Cup football competition, among secondary schools. The project was more than 80 per cent completed, as at the time Governor Aregbesola ended his two terms in November 2018. The succeeding administration had, however, not completed the project, as at April ending 2022.

But aside from new elementary, middle and high schools, a lot more, especially in the rural areas, were renovated to make the school atmosphere much more teaching and learning-friendly. The renovated structures included 139 elementary schools, 271 middle schools and nine high schools. In many cases, however, “renovation” meant a sweeping re-design of the old school, giving way to a completely new school compound concept; complete with new play grounds with recreation and games parks for the children at break time, football pitches with lush green surfaces, mini-tracks and other facilities to fire the imagination of the children; and make schools exciting and schooling very attractive again.

Anthony Udofia Model Primary School and Baptist Elementary School, Ilare, Ile-Ife, were two of the many schools that typified these new and exciting features. Even in its shabby and seedy old state; and with its run-down set of classroom bungalow blocks, it was a “model school”, as its gate pillar gleefully pronounced: “Anthony Udofia Model Primary School, Iwo-Ibadan Road, Osogbo.” But as it got transformed into the new Anthony Udofia Elementary School, with a sweet concrete-and-redbrick quadrangle housing its nest of classes, library and other facilities, the old school and its denizens were, at last, savouring how a model school should look and feel!

Not less exciting to the eye and the senses was the picture of a brood of pupils, at the Baptist Elementary School, Ilare, Ife, playing football in what looked like a tiny stadium, complete with coaches’ dugout! Another set of pupils, from this same school, were pictured running, merry and excited, in their games park, with its many gadgets, at break time! If succeeding governments could sustain, maintain and further build on these facilities, it could firmly plant the idea that government schools, which most Nigerian children and youths attend, need not be run-down and seedy – the very model of neglect. That feel-good sense, among the appreciative youngsters, could build a firm foundation for enduring patriotism, much more than any future preachment at them; just as run-down schools could have firmly planted an eternal grudge, in their young and tender minds, that the government cares little about the governed.

Revamped public schools also involved compound security (in terms of perimeter fencing), water, sanitation and toilet facilities, improved school furniture and transport to and from school, since most of the schools – if not all – were day and not boarding schools. Fences were built around 20 old schools to further secure their facilities. One hundred and sixty other schools benefited from new toilet facilities: how did the teachers and pupils, of those 160 schools, cope when they lacked those vital facilities, without a serious dent on teaching and learning? The supply of fresh furniture – desks and chairs, 62, 922 pieces in all – also painted the dreary picture of how run-down those schools could have been before the Aregbesola years, and for how long!

Transportation also posed no less a challenge. Back to when the Aregbesola “Green Book” was being developed for the 2007 electioneering, there were talks of how schools should be planted in communities. No child, it was argued – particularly those in elementary and middle schools – should trek longer than a certain distance before arriving school. That distance should be short enough, so that the child is not too tired to learn. For elementary schools, it was between 50 metres and 500 metres. While that plan could be implemented without much sweat in the rural areas, it was practically impossible in big, built-up towns like Osogbo, Ilesa, Ede, Ikirun, Ila, Ife, Ejigbo, etc – and Osun has the greatest concentration of big towns in all of Yoruba land. That created a transport challenge in implementing the new Osun education policy, particularly in these big towns. The solution to that was Omoluabi Scholar Bus initiative: a fleet of 45 buses, with drivers sporting yellow shirts, brown trousers with yellow trimmings, smart bow-ties, and brown berets emblazoned with the State of Osun crest.

Still, the revamped school infrastructure, in all their grandness and freshness, were a throwback to pledges in the Aregbesola Green Book. That campaign booklet pledged, among others, to:

- Improve incentives to teachers and work with the NUT (Nigerian Union of Teachers) to restore the dignity of the teaching profession.

- Restructure the administration of school management and create tutor-generals (permanent secretary cadre) from among head teachers in three educational districts, which we will establish.

- Fix all collapsed educational infrastructures in all the schools.

- Support with modern teaching aids and well-stocked libraries.

- Reduce number of students per classroom immediately.

These, among others, were critical lifelines the Osun public educational sector sorely needed; and the government, within its limited means, did much to plug the gaping holes: both on the side of teachers and pupils; and on an improved school environment.

Despite these doughty interventions, Osun’s public education sector did not turn an instant paradise. Three years after the Aregbesola governorship, Osun Defender published a rather depressing story about a school in rural Osun. The story’s headline and rider were self-explanatory: “Inside Osun school where JSS 1-SSS 3 share four classrooms – Four teachers take all subjects for about 500 students.”

It reported the sorry state of the Community Grammar School, Ikonifin, a town in the Ola-Oluwa Local Government area of the state. The school, founded and built in 1979 by the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) Oyo State government of Chief Bola Ige, as part of that era’s free education programme, was also to serve neighbouring communities like Obamoro, Odoran, Isero, Sade, Gogooru, Gaa-Seidu, Gaa-Adamu, Gaa-Baabo and Olaala. What Osun Defender saw, however, was a once-upon-a-school, so decrepit and so run-down. Four classrooms catered for 500 pupils. Also, there was an acute shortage of teachers: four – or five, if you add the embattled principal – to teach some 500 pupils!

The four available classrooms were in the L-School blocks that O’School designed and built for schools in the Osun interior, during the Aregbesola years. The older structures from the Bola Ige era in 1979, plus a Lodge for National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) members: a bungalow of flats that Governor Bisi Akande, during his own tenure from 1999 erected in the school premises was decrepit beyond repair. The run-down Lodge meant even less teacher prospects: that Lodge, which like a magnet pulled NYSC teachers to the school, was no more. All these setbacks spoke of long-term neglect of the school – and others in the rural areas – before and after the Aregbesola years.

The Aregbesola government built 3, 685 new classrooms in all, for Elementary, Middle and High schools. The 3, 685 classrooms housed 184, 300 pupils. These were otherwise remarkable numbers, particularly for a resource-challenged state. Still, the 184, 300 pupils that the new classrooms housed still fell short of the projected target to accommodate 356, 000 pupils by 171, 700! At the opening of this chapter, Adeeyo said Aregbesola’s target was to build enough classrooms to accommodate 356, 000 pupils, in Osun public schools.

That tells a simple story – and perhaps explains why Community Grammar School, Ikonifin, and its likes still plague the rural Osun: to mend the Osun troubled public education sector, there must be constant and continued intervention. Only a policy of progressive investments, by every successive government, can make that goal a reality.

Opon Imo

On Opon Imo, the computer teaching-and-learning tablet, the Aregbesola administration was triumphant – and understandably so. The gadget was hailed in global education circles as innovation-fit-for-adoption by developing countries, craving to stamp some order on their rather shambolic curricular.

“The Opon Imo Technology Enhanced Learning System (OTELS) has developed a learning tool that could revolutionize learning in developing states around the world,” the government gushed. “The Opon Imo or Tablet of Knowledge is a stand-alone e-learning tablet that provides the senior secondary students with the contents required to prepare for school leaving examinations.” Other features of Opon Imo include a multi-media content, 54 e-textbooks covering 17 subjects, 54 (video) tutorials covering 17 subjects, over 40, 000 practice questions and answers and seven extra-curricular books.

Those “seven extra-curricular books” include the Christian Bible, the Moslem Qur’an and the Ifa Corpus – which kept faith with the Aregbesola-era policy of state equal recognition for the three major faiths of the Osun people. The inclusion of these religious canons also seemed to preach, without overtly saying so, religious tolerance and mutual respect among adherents of different faiths. That might have been the pleasant reality among the Yoruba, of which Osun was a proud part. Still, including the three books was clearly aimed at reinforcing such liberal faith temper in Osun public school pupils.

Opon Imo, if well used, can also track the class progress of each of the users; and its battery can be powered using communal solar chargers at school; or at home, with conventional electricity. At a time, some 150, 000 of the gadget had been distributed to SSS 3 final year beneficiaries, to aid them in preparing for their terminal examination. Since the tablet contained 54 e-textbooks on different subjects, the Aregbesola government reckoned that it had saved an estimated N8.4 billion yearly, on what it could have spent on textbooks. Its Free Education policy package included free texts and exercise books. The formula must have worked well, for at a time, there were media reports of grumbling managers of private schools in Osun, complaining that they were losing children to public schools.

In-service teacher training

While Opon Imo offered a teacher-pupil interface, particularly by its 54 interactive video tutorials covering all the 17 subjects in the school curriculum, the Aregbesola government embarked on routine workshop and seminar training, to boost the teaching and administrative skills of Osun teachers. Partners for the training included the National Institute for Educational Planning and Administration (NIEPA), the National Teachers Institute (NTI), the Education Faculties of the Osun State University (UNIOSUN), Osogbo and Obafemi Awolowo University (OAU), Ile-Ife. These partner institutions designed specialized programmes tailored to the needs of Osun teachers, “not only to update their skills, attitudes, but also attune them to the acquisition of new and relevant teaching techniques.”

Between 2011 and 2018 when Aregbesola left office, more than 30, 145 public school teachers were trained in 26 workshops. Among these specific training, the “Priming Underutilized Mathematical Programme” (PUMP) was conceived to train more than 200 Mathematics teachers in Osun public schools, and also to drill over 100 high school pupils; to introduce the pupils to modern insights; and to introduce to teachers, better and more effective techniques of passing mathematical knowledge to their pupils. For PUMP, the government invited, as a resource person, Prof. Adeniran Adeboye, an indigene of Gbongan in Osun but a Mathematics professor from Howard University, Washington DC, USA.

Aside from training, however, the era also witnessed upticks in teacher and non-teacher welfare in Osun public schools. For instance, 17, 057 teachers and non-teaching staff were promoted in the school system. Between 2011 and 2013, the government recruited more than 12, 000 teachers for public secondary schools, aside from 6, 000 OYES volunteers deployed to teach in schools. In the elementary schools too, 3, 230 teachers were employed, aside from 569 non-teaching support staff recruited for Osun elementary, middle and high schools.

School reclassification

Aregbesola’s school reclassification drew rather sharp criticisms because it appeared to jar against the Nigerian conventional 6-3-3-4 system: six years in primary, three years in junior secondary, three years in senior secondary and four in tertiary institutions. Not a few alleged that the Aregbesola government had mutilated the national 6-3-3-4 system and, therefore put in jeopardy, the future of Osun public school pupils. So strong was that sentiment that the succeeding Gboyega Oyetola government set up a committee which recommended that the state revert to 6-3-3-4. It eventually did, very early in the life of that government.

Still, Governor Aregbesola and his Education officials had always explained that the reclassification was more of a tinkering, as recommended by the Osun Education Summit of 2011; and less of a distortion of the 6-3-3-4. That tinkering involved Elementary (Primary 1-4); Middle School (Grades 5-9: merging the conventional primary 5 and 6 with the Junior Secondary 1-3); High School (Grades 10-12). Even here, the three-year senior secondary school period was untouched. It was just renamed Grade 10-12 under the new template. After senior secondary school were the standard four years of tertiary education, except the course of study was Law, Medicine, Architecture or Engineering.

The bone of contention, against the Aregbesola 4-5-3-4 (though it contained 16 standard years of formal education as the 6-3-3-4), was the fate of the First School Leaving Certificate – the “G-2” of old. G-2 was the first pillar of literacy in those early days of sparse education and mass illiteracy in Nigeria. Now, private schools have all but eliminated the G-2, as they prepare their pupils for admission into junior secondary school from primary five. Might the Osun government, under Aregbesola, be encouraging such a trend, which tended to subvert even the 6-3-3-4 official curriculum?

The government insisted that was not the case; that primary six pupils would still take their terminal examination and earn their First School Leaving Certificate; and that the only slight change was the coupling of the last two years of Primary School, with the three years in the Junior Secondary School, both now housed in the new Osun Middle Schools. Somewhat, however, this explanation fell on deaf ears – not the least with the media, which ought to explain matters, particularly new policies that could cause controversies. Many in the media just echoed the mass though wrong grumble: Aregbesola was fixing what was not broken! He was wasting time and money! So, he must be whipped into line!

Still, Otunba Oyeduntan retorted: “The reclassification of schools was another noise that was not necessary. The curriculum was not affected at all. It was just,” he explained, “that different addresses were given to different age groups” – his own way of explaining the merging of the conventional primary 5 and 6 with the Junior Secondary School (JSS), in the new Osun Middle Schools. That, indeed, was the only tinkering with the 6-3-3-4.

The school reclassification controversy would rage all through the Aregbesola years. The concerned publics did not only misunderstand the new policy, many of them clearly did not want to understand it. Yet, a vital reason for the reclassification policy had to do with the newly conceived O-Meals programme; and the government’s anxiety that Primary 5 and 6 pupils, not covered by the feeding regime, were not assailed by hunger pangs each time their luckier juniors were being fed. O’Meals under Aregbesola covered Primary 1-4. So the most senior primary school pupils, not covered by the feeding scheme, were tucked away into the new Middle Schools, from the provocative mid-day meal aroma.

O’Meals: Osun home-grown school feeding programme

Before the Osun Elementary School Feeding and Health Programme (O’Meals), there was a school feeding scheme under Governor Olagunsoye Oyinlola. It covered kids from Primary 1-3. The trouble though was the ensuing bedlam from the upper primary classes, each time the food vendors came.

“By the time they were feeding the children in Primary 1 to 3,” Otunba Oyeduntan recalled, “their siblings in the upper classes who had left home hungry, would follow the aroma to the lower classes. You can then imagine the confusion and the toll that took on teaching and learning.”

That daily hubbub weighed heavily on the mind of Governor Aregbesola and his education officials, led by Deputy Governor Grace Titilayo Laoye-Tomori, as they were making the budget for O’Meals. The 4-5-3-4 school reclassification policy was being decided. Even then, the Ministry of Education officials came with proposals to continue with the school feeding regime of the Oyinlola years, which covered only the first three years of primary education. Though the new Elementary Schools would run for four years, the old arrangement would still have left Year 4 pupils in the lurch: just as it did the Primary 4-6 pupils, under the Oyinlola arrangement. But one day, when the Ministry of Education planning officials brought their estimates, the Governor popped the question.

“What would it cost to feed another class, say Primary 4?”

They gave him the estimates.

“Just this?” he asked. “Yes” was the reassurance.

“Then, let’s feed all in the Elementary School.”

That was how the Aregbesola-era O’Meals programme got extended to primary four, from December 2012. Back then, it increased the pupils being daily fed by 98, 932: from 155, 318 to 254, 250.

The Governor would explain the thinking behind his decision, particularly as it also led to why the old Primary 5 and 6 were now grouped with the newly conceived Middle Schools:

Middle Schools were a merger of primary 5 and 6 and the old junior secondary schools. We could not feed pupils in these two most senior primary classes. So, should we keep primary 1 to 6 the way it was, it would be that some pupils would be having foods while others would not. So, for sanity, orderliness, for human dignity and respect, for sensibility of the children, we moved the unfed old primary 5 and 6 to old JSS to form the middle schools. We called them Grade 5 to 9, while the senior secondary schools were called high schools, from Grade 10 to 12. For the high schools, we set the buildings as mega-schools, with the capacity of 3, 000 pupils.

The school feeding programme generated its own impressive statistics showing, beyond the Education sector, how it drove other sectors of the Osun local economy:

- 254, 250 pupils in grade 1-4 in 1, 382 public Elementary Schools fed daily.

- Over 317 million plates of food served under O’Meals at the cost of N10 billion, as at 2017.

- 3, 007 women directly employed as community cooks.

- 7, 057 other jobs created: 900 cocoyam farmers, 700 small poultry farmers, 310 catfish farmers and 63 cow markets, among others, regularly supplied items to O’Meals caterers.

- School enrolment increased from 155, 318 pupils at O’Meals’ inception to 252, 739 – an increase of 62 per cent.

- Under O’Meals, Osun public school pupils consumed 8, 400 crates of eggs weekly, 336, 000 crates yearly, and over 2 million crates, over six years.

- 10 metric tons of catfish consumed weekly, 400 tons yearly and 2.4 tons over six years.

- 35 heads of cow slaughtered weekly, 1, 400 yearly and 8, 400 over a six-year period, to feed these pupils.

- 15, 000 broiler chickens consumed weekly and some 3.6 million, in over six years, of the O’Meals programme.

- More than 25 states, aside from federal officials, visited Osun to understudy the implementation of O’Meals; and replicate it in their own jurisdictions.

- The programme not only greatly reduced absenteeism in schools; it also led to improved academic performances by the pupils.

Aregbesola himself explained the strategic importance of mid-day meals to his education reforms: “We found out that nutrition was crucial to any meaningful efforts we made. We decided that we must feed students in their formative years, equip them for growth and make them willing and ready learners. So,” he added, “we designed a programme that would accommodate first grade to fourth grade.”

Needless to say, the Osun Elementary School Feeding and Health Programme would inspire a national replication. President Muhammadu Buhari and the All Progressives Congress (APC) government at the centre, from 2016, initiated the National Home-Grown School Feeding Programme (NHGSFP), following the same principle as the Osun template.

“It uses farm produce locally grown by smallholder farmers to provide children nutritious mid-day meals on every school day,” a write-up said of the NHGSFP. “The programme links local farmers to the education sector by facilitating their access to the school-feeding market.”

An NHGSFP attempt was made in 2004 when the then People’s Democratic Party (PDP) Federal Government, under President Olusegun Obasanjo, launched a pilot programme, in 12 states, from Nigeria’s six geo-political zones. Osun was one of the 12 pilot states for the project. However, the Buhari version of NHGSFP had been more far-reaching and sure-footed. Under it, more than 300 million meals had been served to 7.5 million pupils in 46, 000 public primary schools, in 22 states of the country – and still counting. The Buhari government’s target was to spread the programme to all states, as a strategic national policy, no matter the political inclination of the beneficiary states. Again, Osun is among the current 22 beneficiary states.

Still, O’Meals did not appear to have especially deepened after the Aregbesola years. A snap survey, carried out in 2021 at the Anthony Udofia Primary School and the CAC Primary School, both in Osogbo the Osun capital, revealed that the mid-day meal had been rolled back to Primary 1 to 3. So, more senior kids in those schools were back to the Oyinlola-era virtual torture, each time the junior classes enjoyed their meals.

The survey reported the feedback from the food vendors: “We now feed only Primary 1-3, as directed by the government, while other classes watch. But we always try to help these other kids anytime there is excess food, though those cases are very rare.” Predictably: “Many of the pupils usually approached us, complaining of hunger, anytime we were serving the junior ones which, one way or the other, affected their school work.”

Despite the federal NHGSFP supplement to Osun’s original O’Meals, the survey painted a picture of a leaner and far tighter programme. However, the roll-back of beneficiary pupils to Primary 1-3 could have been to align the Osun programme with the federal one.

Unified uniform policy

To Aregbesola, the controversy over his administration’s common uniform policy for Osun public schools was unnecessary.

“If the government is the driver of education; and the uniform is meant to identify those who go to schools, and the body with the largest number of such schools is Government, why,” he queried, “will those schools not have the same set of uniforms to distinguish them from others? Uniform, all over the world,” he insisted, “is to showcase ownership.”

He cited a myriad of examples: Local Authority schools, in the old Western Region of Nigeria, wore dark blue shirts over deep brown khaki shorts (for boys) and dark blue gowns (for girls). Public primary school boys in the North – “from Kwara to Maiduguri”, he called it – wore white shirts over green shorts and green caps to match; the girls wore white-and-green gowns: the top white, and the lower part green, and white head-wear to complete the outfit.

“Our first consideration was that we must be able to identify pupils in government schools by their [common] uniforms. If any of our students is not in school,” he explained, “we will know and promptly take action.” That thinking – to properly monitor school attendance – also informed the creation of “EduMarshals” to “curb truancy, cultism and to bring back discipline in schools.”

The situation outside Nigeria, especially among the country’s West African neighbours, tended to support the Governor’s assertion, especially where the government runs schools. “All children have to wear school uniforms in Ghana. Pupils in public schools have the same type of school uniform with the school’s emblem imprinted on the left chest,” a document wrote of Ghana public schools. “This helps to distinguish pupils of one school from the other. [But] private schools determine which uniforms their pupils wear.”

Indeed in 2010, Ghana made a policy to distribute free school uniforms in public schools nationwide, since it realized that “the cost of uniforms acts as one of the barriers to educational access.” So, from a government data, “170, 221 pupils were supplied with free school uniforms in 2013 and it planned to supply 10, 000 uniforms in 2014.” Incidentally, that was the same period that Aregbesola was implementing his government’s one-uniform policy. Besides, the Ghana government’s thinking would appear similar to the Aregbesola government’s: to use free school uniforms, not only to drive enrolment but also to mitigate vicious and endemic poverty.

Outside Africa, the United Kingdom has a school uniform policy dating back to the Elementary Education Act of 1870. In the United States, prescribed school uniforms are a much more recent development, though there were school dress codes, which need not be the same colour. Indeed, a study showed that as late as 2000, “only 23% of public, private and sectarian schools had any sort of uniform policy in the United States at or before 2000.”

Still, the Nigerian experience was much more plural. Though in the early 1970s the Nigerian military governments took over hitherto mission and other private schools, to make education more accessible to citizens, they did not impose a central uniform on the schools that the government took over. By allowing those schools to retain their different uniforms, Nigeria – particularly southern Nigeria – was a flower of uniforms. The mission schools especially retained their uniforms, for their legacy founders to maintain a sentimental attachment to those schools; even if the government now owned the schools, and the original founders all collected due compensation at the take-over point.

That was the situation that the Aregbesola government met. The schools were fully public schools. The government was paying teachers, who had become career officers, in the Osun public education bureaucracy. Still, the schools maintained their old names and uniforms — clearly as a mark of respect for their legacy founders: Christian/Muslim missions or communities. With such, old sentiments stayed strong. Aside from ownership, old-student feeling was no less strong: so the very thought of age-old uniforms vanishing for a new central set was roiling and painful. That explained the opposition from some quarters – vicious and virulent in some cases – to the new government’s policy of a unified set of uniforms.

Attachment to old schools and uniforms could not be discarded. It was the reality of an age; and those who lived through that school age (pupils, teachers, school support staff and others) would naturally balk at a change that tended to wipe out their old reality. The fear of the unknown plagues every age. Yet, the argument of a government trying to chart a new future, of state massive education support for the bulk of its citizens, especially the poor and the vulnerable, was no less compelling. If the government was thinking of free uniforms for every pupil in Osun public schools, it made no sense to retain the many uniforms of the old order. Rather, it would make more economic sense to reduce the set of uniforms to cater for just the three cadres in the Osun school system: Elementary, Middle and High. Going by economy of scale, the cost of the new uniforms would be cheaper. It would be just three designs that the manufacturers would mass-produce. At that stage, however, that decision would cross from strict education, into a policy stimulating the Osun economy.

Indeed, the thinking in the new government was that as OYES, O’School and O’Meals, the common uniforms policy should also help to drive the Osun economy. It therefore advertised for industrial tailoring and design firms that could partner with the new government, to design and mass produce the new school uniforms. Enter, the Omoluabi Garment Factory.

Omoluabi Garment Factory

For Mrs. Folake Oyemade, Managing Director of Sam and Sara Ventures Ltd, the Osun one-uniform policy offered a rich opportunity to further expand her company’s uniforms line, among its other well established clothing brands. The garment manufacturing firm tells its own history: “Sam & Sara started business in 1987 as Bijoux Unisex Collections. It has grown to become a foremost garment manufacturing outfit. Over the years, Sam & Sara has cultivated an enviable pedigree of quality and constantly improved processes of garment production.”

It also crows about its different lines: “Sam & Sara’s flagship brand Impresza has become a household name in the areas of corporate wear, promotional wear, school uniforms, hospitality uniforms, paramilitary/security uniforms, professional wear, robes and academic gown. We,” it added, “also manufacture accessories such as logo ties, logo scarfs, lanyards, etc.” It spoke about its industry experience, regular or bespoke, spanning 26 years – its cumulative years of business when the Osun opportunity came calling: “In accordance with clients’ needs, we research, develop, design and produce garments to meet the intended purpose and expectations.”

Aside from its head office and showroom on Victoria Island, Lagos and another boutique and office at GRA Ikeja, also in Lagos, it has its factory at Mowe, Ogun State: KM 42 on the Lagos-Ibadan Expressway, just opposite the Deeper Life Church. Its clients, according to its official profile, included the Lagos State Traffic Management Authority (LASTMA), banks like Access, Ecobank and GTBank, Oil and Gas majors like Total and the Nigerian Liquefied Natural Gas (NLNG) Ltd; and Corona School, Lekki, among others.

Sam and Sara applied and won the competitive bid for the Osun venture. After winning, however, the Osun government’s condition was clear: the firm must set up shop in Osogbo. “We don’t want our money going out of our state,” Mrs Oyemade quoted Governor Aregbesola as telling her – just as the Governor had told Engineer Adeeyo, the O’School consultant-in-chief, that none of his project recruits must come from outside Osun. Sam and Sara should also commit to training local tailors – or other youths that showed interest: to not only equip thousands of Osun jobless youths with tailoring skills but to also mainstream tailoring technical standards among the slew of Osun artisan tailors and fashion designers. In return, Sam and Sara was guaranteed the design and mass production of the new Osun public school uniforms; and later, the bulk of uniforms required by the Osun public sector: hospitals, state schools of nursing, government parastatals and agencies; aside from private sector prospects in private security firms, hotels, factories and others that needed overalls for their daily operations.

That was how, in 2013, Sam and Sara Ventures Ltd made a landing in Osogbo, as Omoluabi Garment Factory. Compared to Lagos and Ogun where Sam and Sara was well entrenched, Osun was near-virgin territory. Nevertheless, Mrs Oyemade and her firm shared the new Governor’s job creation and industrialization drive.

She explained: “Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola was the driving force that made us come to Osun. The government wanted to centralize the school uniforms; and they wanted a credible company to do it. We responded to the government’s advert like other companies. We made submissions,” she stressed, “we won the bid.” But then after winning, the Governor added another key proviso: the bid winner must “come and set up a factory within the state because we do not,” he insisted, “want our jobs and our money taken to other states.”

The company understood the Governor’s point of view, since Osun was not a “big economy state”. It, however, had its own counter-demand: the government must provide industrial land on which the factory would be built, and sundry take-off support. The government did and, as a sign of good faith and demonstration of long-term business relationship, acquired 14% cent equity in the company – which, more or less, equated the government’s land investment and sundry take-off contributions to the firm. Omoluabi Garment Factory, a subsidiary of Sam and Sara Ventures Ltd, was born.

The firm was also not averse to the new government’s vision of training Osun youths in tailoring; and mainstreaming technical standards in tailoring, among Osun teeming youths. The first set of youths was trained at the Sam and Sara garment plant at Mowe, in Ogun State. Then, seeing the huge response, especially among single mothers and other unemployed young women, the company decided to make it a big corporate social responsibility (CSR) project. Anyone that expressed interest, that could read and write, and that the company pre-qualified as trainable, was admitted into the training. That meant that the beneficiaries were not limited to artisan tailors alone. That also meant that Sam and Sara, without any financial support from the Osun government, brought in some Chinese master-tailors to put the trainees through the grill, in different gamut of industrial tailoring: design, stitching and sowing, hemming, ironing, folding and packaging, and other processes – the whole works. To the bargain, the trainees enjoyed a little training stipend as well. More than 1, 000 youths benefited from the training. Sam and Sara was no industrial Santa Claus. But it judged this initial investment – even beyond the original artisanal dream of the Osun government – to be very crucial, since the company itself was fishing for trained and skilled hands to work in its Osogbo Omoluabi Garment Factory. Besides, having done its feasibility studies on the new project, it found that dominating the Osun public school uniforms market, aside from other uniforms prospects from the Osun public and private sectors, would more than pay off this initial investment, with a handsome profit, over the years.

Initially, business was good, with the company enjoying a rave image, among its Osun workers and the general public, thanks to its highly applauded training CSR. At two daily shifts, Mrs Oyemade recalled having no less than 1, 000 workers, at the firm’s Osogbo plant. Even then, not all of the trainees opted to work at the Omoluabi Garment Factory. Many indeed decided to set up shops of their own, happily displaying framed pictures of their cherished Sam and Sara training, under the watchful eyes of the Chinese master-tailors and trainers. But even at that, Omoluabi Garment Factory, with its humming industrial machines and its more than a thousand workers, was by far the biggest industrial tailoring concern in Osun. The government’s dream of fresh job opportunities for Osun youths was alive and well. So were the firm’s dreams, of years and years of profitable business ahead of it.

But then, the sun set for the company, virtually at noon. The Aregbesola government exited on 27 November 2018. From that time, a vacuum grew between the firm and new Gboyega Oyetola government: the firm’s major client that held the ace of its critical uniforms market, without which Omoluabi Garment Factory could not survive. Before the new government ran its first full year, it cancelled the one-uniform for public schools policy, pleading recommendations from a committee it had set up to look again into the uniforms controversy. But no formal notice came from the government to the firm.

“We never got any formal communication from the government,” Mrs. Oyemade said. “We just heard it from the news.”

With that change, the company shut down – in a limbo perhaps, till some future business arrangement could be worked out.

Mrs. Oyemade relived the parting pangs when the factory had to close; and the workers, laid off: “A lot of them cried when we told them they had to leave because they had no other means of livelihood. Those running the current government, in their wisdom, know why they did what they did,” she shrugged. “But for me, it’s not good for our business; neither was it good for the people we employed.”

Still, with the End SARS riots of 2020, more troubles came for the Omoluabi Garment Factory, though now shut down. “People went there thinking everything there belonged to the government and looted the whole place. All the machines!” she rued “and we didn’t get any respite from any quarter, other than our insurers.” Governor Oyetola would, however, visit the plundered premises, as part of his tour of the areas that the End SARS rioters sacked. There, he appealed to the looters to voluntarily return the machines – very costly industrial machines – or he would set the law after them. “Maybe about 70 to 80 machines were returned,” Mrs Oyemade made a guess. “But that was so low compared to what was stolen.”

Sam and Sara did not recoup its investment in the Omoluabi Garment Factory. It was a huge long-term investment, billed to repay the investors over a number of years. Yet, just only after six years, it fell into a limbo. Still, Mrs. Oyemade was proud of what the company achieved over the period of its brief operations. The old government was faithful to the terms of the business union. Still, operations may have halted – maybe temporarily. But engagement between the firm and its former publics: its Osun trainees and former workers remained vibrant.

“When we have jobs for them, we call them. Within the twinkle of an eye, the place is full,” she enthused, her eyes a glint of pride. “We had more tailors there [in Osogbo] than we have in our factory at Mowe, because the economy of Ogun and Lagos are more open.”

She lauded, even more, the vision that made such an intervention possible, even if regrettably short-lived. But far from the doom and gloom of the short-lived venture, Mrs. Oyemade crowed over something that happened at the opening ceremonies of the new factory. After clerics representing the three faiths had offered prayers (as it was wont during the Aregebesola years), the Governor noticed a rather restive Mrs. Oyemade. He asked her why. She told the Governor that she had in the assemblage her personal pastor; and would rather he prayed to bless the new enterprise. The Governor told her not to worry; that her pastor would pray as she had wished – and indeed, he did. What struck Mrs. Oyemade in all of that was that people often traduced Aregbesola as some Muslim fundamentalist, if not outright Islamic fanatic. Yet, here was the Governor allowing her pastor to pray again, even after the scheduled Christian cleric had earlier done his bit. A “Muslim fanatic” indeed – to have allowed the Christians to pray twice, while the other faiths did only once! Muslim fundamentalist, indeed!

That still warmed the cockles of Mrs. Oyemade’s heart as she declared, even many years after the event: “Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola really is a man of vision; a cosmopolitan man with a good heart, who wanted everything to be okay for everybody.”

The Omoluabi Garment Factory was umpteenth proof of how about every policy of the Aregbesola era was carefully wrought to boost the local economy; to tackle youth joblessness; to reduce general poverty. Had that company not lost its core uniforms niche, how might industrial tailoring have helped to expand the Osun economy, deliver jobs and training to the teeming youth and pay taxes into government coffers! Alas! It is a veritable tale of what might have been!

Calisthenics and enhanced school sports

The primer for calisthenics and enhanced school sports, of the Aregbesola era, could well be the Green Book again. Under “Physical Well-being”, the campaign pamphlet pledged: “Our government will promote physical exercises as a deliberate policy, which will form a crucial aspect of our healthy living programme. This is in keeping with the adage that a sound mind only resides in a sound body.”

Indeed, this principle drove the periodic – monthly, at a time – Walk-for-Life exercises, which the Governor himself led, followed by who-was-who in his administration with the locals in tow. It also became a potent strategy to mobilize the people to support government programmes. The Governor and his high officials also used the walk to interface with the ordinary folks, who never got the opportunity to access Government House. Yet, they cherished that rare opportunity of meeting and mixing with their Governor, right there on the streets.

That principle of healthy exercise was also worked into the Osun education reforms, aside from other components like O’School, O’Meals and the unified uniforms regime. Osun Government Unusual explained the rationale behind the administration’s calisthenics programme in Osun public schools:

Aware of the truism that true education transcends the classroom; the administration has introduced Calisthenics in Osun schools. The attraction of Calisthenics is in its time-honoured virtues of team spirit, unity, resilience, cooperation, tenacity among others, which are needed to survive and succeed in life. The initiative has been introduced to further stimulate complete ‘Omoluabi’ ethos among Osun students

Calisthenics, in public schools, was first made popular by the government of Chief Bola Ige, then Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) Governor of old Oyo State (now Oyo and Osun states) from 1 October 1979 to 30 September 1983. After Chief Ige left office, no government, military or civilian, showed interest in calisthenics again as a potent tool of co-curricular education, especially in the area of building team spirit whilst approaching common problems, which really is a metaphor for grappling with day-to-day challenges, in a developing economy. Like the governments after Ige’s, the Oyetola government too appeared less interested in calisthenics than the government that it succeeded. But that could simply be because its own focus was different from its predecessor’s.

Public policy versus manifest goodness

Public policy involves the mass of the people, with varying individual differences. These people, as a rule, would filter the policies in their individual nets. After, they react positively or negatively, with even not a few declaring themselves neutral or indifferent. Such greeted the Aregbesola education reforms, even with its far-reaching impact on the Osun socio-economic fabric, starting with how the reforms were carefully wrought to rev alive the hitherto comatose Osun economy.

The political opposition often interprets opponents’ roaring success as own partisan near-death. To stay politically alive and relevant therefore, they are obliged to criticize and bad-mouth. So, such may claim that the Aregbesola reforms were nothing to crow about; that the glittering schools only pushed poor Osun into further debts – which it didn’t – and that the mega schools were absolutely unnecessary, since smaller and less costly schools could equally have done the job. Such stances might be logically flawed; and therefore difficult to support or justify. However, as contrary opinions in a democracy, they are no crimes and are therefore legitimate.

Indeed, in the course of the field research for this work, an otherwise staunch Aregbesola loyalist pulled the author close, at the Bayo Salami junction, while the pair drove out of the Oke-Fia GRA, Osogbo. “What Oga ought to have done,” he remarked, pointing to a cluster of school bungalow blocks across the road, “was to have built schools like these, and not the mega-schools.” Though the author shot back at him with a look brimming with harsh rebuke, the man clearly did not understand the vision behind those reforms – and he was not the only one, even within Aregbesola’s so-called inner circles. Strictly, these folks were entitled to their democratic dissent.

Still, the impact that those reforms made was a legacy that would be hard for subsequent governments to match. Locally, the once sleepy Osun, yesterday’s bastion of government-as-routine, started grabbing news headlines. True, some of the news was negative: a product of the panicky political opposition and their media confederates bad-mouthing strides they did not like. But in all fairness, some if not most were core developmental news that showed perhaps the sleepy Osun was, at last, jerking awake. The state started grabbing national headlines, which made many other states to tour it; and find out how they could copy some of its development programmes.

Among others, the war-torn Borno State under Governor Kashim Shettima, even as it reeled under its severe Boko Haram challenges, came to study the Osun mega-school concept. The Islamists might have decreed “western education a sin” as dogma for their insurrection. But Borno, under Governor Shettima, found the perfect answer to the Islamists’ challenge in enlarging opportunities in Borno public schools, for their teeming children, teens and youths. Both Governor Shettima and his successor, Prof. Babagana Zulum, would go ahead to replicate the concept of big and well-equipped public model schools in Borno State – even with the state’s war and crisis-limited resources. That was yet another proof that the Aregbesola reforms were legacies cherished and applauded not only by the direct beneficiaries in Osun, but also by others nationwide who highly acknowledged and applauded those developmental strides.

Again, three years after Governor Aregbesola had exited power, the Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC) in early 2022, came up with “UBEC Modern Smart Schools” – schools which concept was similar to the Aregbesola mega schools. “The schools …” The Nation reported, “will have the capacity to accommodate a large number of students and ICT infrastructure”; and would be built in the six geo-political zones, aside from building one of such schools in the 36 states of Nigeria. The UBEC smart schools would try to maximize available land and ICT infrastructure to the educational needs of the greatest number of pupils possible, as the Osun mega schools did. That tended to have applied, to public education, the famous quip of Jeremy Bentham: “the greatest happiness of the greatest number.”

This would bear restating: despite the fickleness of the public, the penchant of opposing political blocs to find faults, and criticism-for-criticism’s-sake by a section of the media, the different components of O’School would pass the muster as, so far, the greatest school development intervention policy in the history of Osun. It’s a fitting legacy which future governments would find difficult to match. Yet, public education in a developing economy (with its explosive youth population) needs constant intervention, to avert a crisis. That is the challenge O’School poses to future State of Osun governments.

Education

SCHOOL INFRASTRUCTURE NUMBERS

Number of new classrooms built 3685

Number of Model Elementary Schools constructed 67

Number of new Middle Schools 49

Number of newly constructed High Schools 11

Number of Elementary School classrooms renovated 139

Number of Middle School classrooms renovated 271

Number of High Schools renovated 9

Number of old schools that were fenced 20

Number of schools where toilets were constructed 160

Number of new set of furniture distributed to schools across the State 62,922

Number of School buses procured and distributed to schools for free 45

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

EMPLOYMENT, PROMOTION AND TRAINING OF TEACHERS NUMBERS

Number of teachers trained 26,591

Teaching and Non-Teaching Staff promoted 17,057

Teachers recruited between years 2011-2013 for Secondary schools 12,000

Numbers of OYES volunteers deployed to schools as teachers 6,000

Regular teachers employed for elementary schools 3,230

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects, and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

SCHOOL RUNNING GRANTS BURSARY, SPONSORSHIP, AND PAYMENT OF EXTERNAL EXAM FEES NUMBERS

Number of medical students of Osun State University (UNIOSUN) sponsored to Ukraine for medical programme 98

Payment of bursary to indigenes of Osun in tertiary institutions N10,000 to final year students

N20,000 to medical students

N100,000 for law school students

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

O-UNIFORM NUMBER

Number of school uniforms distributed to schools 750,000

Number of jobs created from O-Uniform programme 3,000

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects, and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

CALISTHENICS

NUMBERS

Number of students trained 28,000

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

SCHOOL RUNNING GRANTS BURSARY, SPONSORSHIP, AND PAYMENT OF EXTERNAL EXAM FEES NUMBERS

Percentage of reduction in fee for all students (including non-indigenes) in Osun State University

30%

Increase in School Running Grant of Elementary Schools

N51.8 million to N2.544 billion

Increase in School Running Grant of Middle and High schools

N819 million to N2.562 billion

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

OPON IMO NUMBERS

Number of textbooks in Opon Imo 17

Number of video tutorials in Opon Imo 51

Number WAEC past questions in Opon Imo 5000 (last 10 years)

Amount of funds expended on Opon Imo to date N2.4 billion

Annual savings-annual amount which could have expended on textbook purchase by parents/guardians

N8.4 billion

Number of students benefitted up to date 300,000 +

Number of Opon Imo delivered and being distributed

50,000

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

OSUN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL FEEDING AND HEALTH PROGRAMME (O-MEALS) NUMBERS

Number of pupils in grade 1-4 in 1382 public elementary schools being fed daily

254,250

Number of elementary schools where pupils are being fed daily

1382

Women directly employed as O-MEALs cooks 3007

Number of plates of food already served under OMEALs between 2012 and 2018

317 million

Number of cocoyam farmer beneficiaries 900

Number of small poultry farmer beneficiaries 700

Number of catfish farmer beneficiaries 310

ANNUAL CONSUMPTION UNDER O-MEALS

NUMBERS

Eggs (crates) 336,000

Catfish (tons) 400

Broiler chicken 560,000

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

PERFORMANCE OF OSUN STUDENTS IN CORE SUBJECTS IN 2018 WEST AFRICAN SENIOR SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMS (WASSCE)

Core Subjects Percentages of Candidates with (A1-C6)

General Mathematics 70.73%

English Language 53.56%

Further Mathematics 61.90%

Biology 59.28%

Chemistry 54.44%

Physics 75.22%

Agricultural science 79.03%

Commerce 61.31%

Financial Accounting 69.76%

Book Keeping 62.89%

Data Processing 64.28%

Economics 68.49%

Geography 52.31%

Government 61.66%

History 63.86%

Civic Education 70.93%

French 80.56%

– Source: Osun Government Unusual: A documentation of programmes, projects and impact under Ogbeni Rauf Aregbesola 2010-2018

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not represent the opinions or views of OSUN DEFENDER.